- Definition

- Introduction to Current and Capital Accounts

- Exchange Rate and Types of Exchange Rate

- Depreciation Vs Devaluation

- Consequences of Rupee Depreciation

- How to contain Depreciation of Rupee

- Appreciation Vs Revaluation

- Consequences of Rupee Appreciation

- How to contain Appreciation of Rupee

- What is Convertibility

- Current Account Convertibility and Capital Account Convertibility

- Tarapore Committee Recommendations

What is Balance of Payments (BoP)?

The Balance of Payments or BoP is a statement or record of all monetary and economic transactions made between a country and the rest of the world within a defined period (a financial year).

These records include transactions made by Households, Companies and Government.

According to the RBI, balance of payment is a statistical statement that shows

- The transaction in goods, services and income between an economy and the rest of the world,

- Changes of ownership and other changes in that economy’s monetary gold, special drawing rights (SDRs), and financial claims on and liabilities to the rest of the world.

Q) Assertion (A): Balance of Payments represents a better Picture of a country economic transactions with the rest of the world than the Balance of Trade.

Reason (R): Balance of Payments takes into account the exchange of both visible and invisible items whereas balance of Trade does not. Codes:

(a) Both A and R are individually true and ‘ R ‘ is the correct explanation of A.

(b) Both A and R are individually true but ‘ R ‘ is not the, correct explanation of A .

(c) A is true but R is false.

(d) A is false but R is true.

Q) The balance of payments of a country is a systematic record of

(a) All import and export transactions of a country during a given period of time, normally a year

(b) Good exported from a country during a year

(c) Economic transaction between the government of one country to another

(d) Capital movements from one country to another

The transactions in BOP are categorised into,

Current account: showing export and import of visibles (also called merchandise) and invisibles (also called non-merchandise). Invisibles take into account services, transfers and income.

If the sum of all these transactions is negative then it is called as current account deficit (CAD) whereas if the sum is positive it is called current account surplus.

Capital account: showing a capital expenditure and income for a country. It gives a summary of the net flow of both private and public investment into an economy. External commercial borrowing (ECB), foreign direct investment, foreign portfolio investment, etc form a part of capital account.

Official Reserve Transactions: These are conducted by central banks like RBI whenever there is BoP deficit or BoP surplus. These transactions are conducted in the form of international reserve assets, such as gold and major international currencies.

The sum of the three BoP components should be zero. There is another element in BoP that is ‘Errors and Omissions’, which is the balancing item reflecting our inability to record all international transactions accurately.

Current Account Transactions:

Exports and imports of goods (visible trade): When we export goods, we credit money to the current account. When we import goods, we debit money from the current account. The difference between export and import is called merchandise Trade Balance.

If exports are more than imports there will be trade surplus and if imports are more than exports there will be trade deficit.

Q) Given below are two statements, one labelled as Assertion

(A) and the other labelled as Reason (R).

Assertion (A): An important policy instrument of economic liberalization is reduction in import duties on capital goods.

Reason(R): Reduction in import duties would help the local entrepreneurs to improve technology to face the global markets.

In the context of the above two statements, which one of the following is correct?

(a) Both A and R are true, and R is the correct explanation

(b) Both A and R are true, R is not a correct explanation

(c) A is true but R is false

(d) A is false but R is true

Export and Import of Services (invisible trade): When we export services, we again credit money to the current account. When we import the services, we debit money from the current account. Now, export of services has two meanings. One is that we provide service to the foreign nationals in their own land and another is that foreigners come to our country and we provide service to them here.

Both have same meaning. Like in tourism, the tourists come to India and whatever we earn from their tourism activity is also deemed to be a service export. But since we cannot see this export taking place, we call it Invisible Export. India is slowly becoming a service oriented economy, so invisible exports are slated to play very important role in the years to come.

Following are examples of Invisible exports and imports:

- Money spent on travel by tourists

- Tuition paid to universities by international students

- Banking, Insurance, Consulting services in foreign land

- Royalties and license fee paid for use of copyright or patent

Q) In terms of economy, the visit by foreign nationals to witness the XIX commonwealth games in India amounted

(a) Export

(b) Import

(c) Production

(d) Consumption

Investment income: Investment income includes any income made from investing abroad, profits from business activities of subsidiaries located abroad, interest received from investment and loans abroad, and dividends from owing shares in overseas companies.

If we receive interest, dividends and other incomes from abroad, it will be a credit entry in the current account. Similarly, if we pay the interest, dividends and other expenditures to abroad, it will be debit entry from the current account.

Unilateral transfers: Unilateral transfers include foreign aid, personal gifts sent to friends and relatives abroad, donations, charitable donations, and international remittances, withdrawal/redemption of NRI deposits locally etc. If a foreigner living in India is getting pension from his own country here, it would be credited to current account and vice versa.

Trade Deficit/Trade Surplus:

Simply put, trade deficit or negative balance of trade (BOT) is the gap between exports and imports. When money spent on imports exceeds that spent on exports in a country, trade deficit occurs.

It can be calculated for different goods and services and also for international transactions.

The opposite of trade deficit is trade surplus.

Q) With reference to Balance of Payments, which of the following constitutes/constitute the Current Account

1. Balance of trade

2. Foreign assets

3. Balance of invisibles

4. Special Drawing Rights

Select the correct answer using the code given below.

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 and 3

(c) 1 and 3

(d) 1,2 and 4

Q) With reference to the international trade of India at present, which of the following statements is/are correct?

1. India’s merchandise exports are less than its merchandise imports.

2. India’s imports of iron and steel, is chemicals, fertilisers and machinery have decreased in recent years.

3. India’s exports of services are more than its imports of services.

4. India suffers from an overall trade/current account deficit:

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 and 4 only

(c) 3 only

(d) 1,3 and 4 only

Q) Consider the following actions which the government can take:

1. Devaluing the domestic currency.

2. Reduction in the export subsidy.

3. Adopting suitable policies which attract greater FDI and more funds from FIIs.

Which of the above action/actions can help in reducing the current account deficit?

(a) l and 2

(b) 2 and 3

(c) 3 only

(d) 1 and 3

Twin Deficits

Twin deficit refers to the fiscal and current account deficit. Fiscal deficit means higher expenditure over income. The gap between expenditure and income is bridged through borrowing from market.

The term current account deficit is derived from current account balance. According to the OECD, the current account balance of payments is a record of a country’s international transactions with the rest of the world. The current account includes all the transactions (other than those in financial items) that involve economic values and takes place between resident and non-resident entities.

Also covered are offsets to current economic values provided or acquired without a quid pro quo. This indicator is measured in million USD and percentage of GDP. The Cambridge Dictionary defines current account deficit signifies that the money going out of a country through imports, investment, and services is greater than money coming into the country.

What is causing the deficits?

The Finance Ministry’s Monthly Economic Review, said: “as government revenues take a hit following cuts in excise duties on diesel and petrol, an upside risk to the budgeted level of gross fiscal deficit has emerged. Increase in the fiscal deficit may cause the current account deficit to widen, compounding the effect of costlier imports, and weaken the value of the rupee thereby further aggravating external imbalances, creating the risk (admittedly low, at this time) of a cycle of wider deficits and a weaker currency.”

Excise duty on petrol and diesel has been lowered twice between November last year and May this year. Since this is one of major source of revenue not just for Centre but for States also, a reduction in the tax rate will affect government revenues. At the same time, expenditure is up mainly on account of higher fertiliser subsidy and outgo for food subsidy. All these are expected to push expenditure beyond ₹39 lakh crore, (as projected in the Budget). Since the revenue will take a hit, the fiscal deficit is set to widen.

For the current account deficit, rising price of not just crude but also of edible oil and other commodities will push up the import bill, which means there will be a higher pay out in dollars. Also, higher fiscal deficit is also expected to fuel the current account deficit.

How will it impact the Indian economy?

A higher fiscal deficit is expected to lower the resources available for private investment. This could lead to higher interest rate which in turn will affect private investment and finally growth. A higher current account deficit will lead to the weakening of rupee which will further impact the import bill. Though exports will get the benefit of a weaker rupee, but with the rise of costly imported inputs, the benefit could be tempered.

What should the government do to tackle this?

To keep the fiscal deficit under control, the government needs to cut expenditure. Since capital expenditure should not be cut considering the growth requirement, a cut in revenue expenditure is advisable. In fact, the Monthly Economic Review has also said that rationalizing non-capex expenditure has become critical, not only for protecting growth supportive capex but also for avoiding fiscal slippages.

The government has a limited role in tackling the surging current account deficit. Still, it can formulate a new strategy to boost exports by exploring newer markets, ease the procedures for exporters and release their tax dues in time. In order the lower the import bill, boosting domestic production of goods and services under the Production Linked Incentives (PLI) schemes is vital.

Capital Accounts Transactions

The capital account transactions include all transactions which alter the assets or liabilities, including contingent liabilities, outside India of persons resident in India. Similarly, it includes transactions which alter assets and liabilities in India of persons resident outside the India.

The assets and liabilities include securities, immovable properties, foreign currency, lending or borrowing in foreign currency or rupees, intangible assets, trade credits etc.

Current Account items can be categorised based on maturity as short term or long term flows, based on instrument type as debt or non-debt instrument. NRI deposits from part of capital accounts. Other capital account items includes leads and lags in exports, special drawing rights (SDR) allocation, funds held abroad, advances received pending issue of shares under FDI and other capital not included elsewhere.

Foreign Direct Investment: When foreigners purchase the Indian capital assets such as factories, machines, companies, we credit the money to the capital account. If Indians make FDI investment abroad, we debit the money from the capital account.

Portfolio Investment: When foreigners purchase the Indian securities such as stocks, bonds, CDs, money-market accounts, the money is credited to capital Account. When Indians purchase the foreign securities abroad, the money is debited from the capital Account.

Q) With reference to Foreign Direct Investment in India, which one of the following is considered its major characteristics?

(a) It is the investment through capital instruments essentially in a listed company.

(b) It is largely non-debt creating capital flow

(c) It is the investment which involves debt-servicing.

(d) It is the investment made by foreign institutional investors in the Government securities.

Q) Which of the following would include Foreign Direct Investment in India?

1. Subsidiaries of foreign companies in India

2. Majority foreign equity holding in Indian companies

3. Companies exclusively financed by foreign companies

4. Portfolio investment

Select the correct answer using the codes given below:

(a) 1,2,3 and 4

(b) 2 and 4 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1,2 and 3 only

Q) Both Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Foreign Institutional Investor (FII) are related to investment in a country.

Which one of the following statements best represents an important difference between the two?

(a)FII helps bring better management skills and technology, while FDI only brings in capital.

(b) FII helps in increasing capital availability in general, while FDI only targets specific sectors.

(c) FDI flows only into the secondary market while FII targets primary market

(d) FII is considered to be more stable than FDI.

Other items of Capital Account: When there is an increase in loans & trade credits to Indian residents by foreigners, the money will be credited to financial account and vice versa. Loans can be in the form of external assistance, external commercial borrowings and trade credits.

Q) Which of the following constitute Capital Account?

1. Foreign Loans

2. Foreign Direct Investment

3. Private Remittances

4. Portfolio Investment

Select the correct answer using the codes given below.

(a) 1,2 and 3

(b) 1,2 and 4

(c) 2,3 and 4

(d) 1,3 and 4

BoP Crisis: A BoP crisis, also called a currency crisis, occurs when a nation is unable to pay for essential imports or service its external debt repayments. Typically, this is accompanied by a rapid decline in the value of the affected nation’s currency.

Crises are generally preceded by large capital inflows, which are associated at first with rapid economic growth. However a point is reached where overseas investors become concerned about the level of debt their inbound capital is generating, and decide to pull out their funds.

The resulting outbound capital flows are associated with a rapid drop in the value of the affected nation’s currency. This causes issues for firms of the affected nation who have received the inbound investments and loans, as the revenue of those firms is typically mostly derived domestically but their debts are often denominated in a reserve currency.

Once the nation’s government has exhausted its foreign reserves trying to support the value of the domestic currency, its policy options are very limited. It can raise its interest rates to try to prevent further declines in the value of its currency, but while this can help those with debts denominated in foreign currencies, it generally further depresses the local economy

Import Cover: Import Cover measures the number of months of imports that can be covered with foreign exchange reserves available with the central bank of the country. Eight to ten months of import cover is essential for the stability of a currency.

India’s BoP Crisis in 1991: India’s post-Independence development strategy was both inward-looking and highly interventionist, consisting of import protection, complex industrial licensing requirements, financial repression, and substantial public ownership of heavy industry.

However, macroeconomic policy sought stability through low monetary growth and moderate public sector deficits. Consequently, inflation remained generally low except in response to unfavourable supply shocks (e.g., from oil price increases or poor weather conditions).

The current account was in surplus for most years until 1980, and there was a reasonable cushion of official reserves. Official aid dominated capital inflows.

During the first half of the 1980s, the current account deficit stayed below 1/2 percent of GDP. While export growth was slow, the trade deficit was kept in check, as a rapid rise in domestic petroleum production permitted savings on energy imports. At the same time, the high proportion of concessional external financing kept debt service down.

In the second half of the 1980, current account deficits widened. India’s development policy emphasis shifted from import substitution toward export-led growth, supported by measures to promote exports and liberalize imports for exporters.

The government began a process of gradual liberalization of trade, investment, and financial markets. Import and industrial licensing requirements were eased, and tariffs replaced some quantitative restrictions. Export growth was rapid, due to the initial measures of deregulation and improved competitiveness associated with the real depreciation of the rupee.

However, the value of imports increased at a faster clip. The volume of petroleum imports increased by more than 40 percent from 1986-87 to 1989-90 with the growth of domestic petroleum production slowing and consumption growth remaining strong.

A deterioration of the fiscal position stemming from rising expenditures contributed to the wider current account deficits. For instance, imports of aircraft and defense capital equipment rose sharply. The balance on invisibles also deteriorated as debt-service payments ballooned.

Current account deficits in the second half of the 1980s exceeded the availability of aid financing on concessional terms and consequently other sources of financing were tapped to a greater extent.

In particular, the growing current account deficits were increasingly financed by borrowing on commercial terms and remittances of non-resident workers—which meant greater dependence on higher cost short maturity financing and heightened sensitivity to shifts in creditor confidence.

India’s external debt nearly doubled from some $35 billion at the end of 1984-85 to $69 billion by the end of 1990-91. Medium- and long-term commercial debt jumped from $3 billion at the end of 1984-85 to $13 billion at the end of 1990-91 and the stock of non-resident deposits rose from $3 billion to $10.5 billion over the same period.

Short-term external debt grew sharply to $6 billion and the ratio of debt-service payments to current receipts widened close to 30 percent. By 1990-91, India was increasingly vulnerable to shocks as a result of its rising current account deficits and greater reliance on commercial external financing.

Two sources of external shocks contributed the most to India’s large current account deficit in 1990-91. The first shock came from events in the Middle East in 1990 and the consequent run-up in world oil prices, which helped precipitate the crisis in India.

In 1990-91, the value of petroleum imports increased by $2 billion to $5.7 billion as a result of both the spike in world prices associated with the Middle East crisis and a surge in oil import volume, as domestic crude oil production was impaired by supply difficulties.

In comparison, non-oil imports rose by only 5 percent in value (1 percent in volume terms). The rise in oil imports led to a sharp deterioration in the trade account, worsened further by a partial loss of export markets (as the Middle East crisis disturbed conditions in the Soviet Union, one of India’s key trading partners). The Gulf crisis also resulted in a decline in workers’ remittances, as well as an additional burden on repatriating and rehabilitating non-resident Indians from the affected zones.

Second, the deterioration of the current account was also induced by slow growth in important trading partners. Export markets were weak in the period leading up to India’s crisis, as world growth declined steadily from 4% percent in 1988 to 2% percent in 1991.

The decline was even greater for U.S. growth, India’s single largest export destination. US. growth fell from 3.9 percent in 1988 to 0.8 percent in 1990 and to -1 percent in 1991. Consequently, India’s export volume growth slowed to 4 percent in 1990-91.

In addition to adverse shocks from external factors, there had been rising political uncertainty, which peaked in 1990 and 1991. After a poor performance in the 1989 elections, the previous ruling party (Congress), chaired by Rajiv Gandhi (the son of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi), refused to form a coalition government.

Instead, the next largest party, Janata Dal, formed a coalition government, headed by V.P. Singh. However, the coalition became embroiled in caste and religious disputes and riots spread throughout the country. Singh’s government fell immediately after his forced resignation in December 1990.

A caretaker government was set up until the new elections that were scheduled for May 1991. These events heightened political uncertainty, which came to a head when Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated on May 21, 1991, while campaigning for the elections.

India’s balance of payments in 1990-91 also suffered from capital account problems due to a loss of investor confidence. The widening current account imbalances and reserve losses contributed to low investor confidence, which was further weakened by political uncertainties and finally by a downgrade of India’s credit rating by the credit rating agencies.

Commercial bank financing became hard to obtain, and outflows began to take place on short-term external debt, as creditors became reluctant to roll over maturing loans. Moreover, the previously strong inflows on non-resident Indian deposits shifted to net outflows.

Factors that affect the BoP

Inflation: If a country’s inflation rate increases relative to the other countries with which it trades, its current account would be expected to decline. Due to higher prices at home, consumers and corporations within the country are most likely to purchase more goods and services overseas (due to high local inflation), while the country’s exports to other countries will fall.

National Income: If the national income of a country rises by a higher percentage than those of other nations, its current account is expected to decline, other things being same. As the real income level (adjusted for inflation) rises, so does consumption of goods. A percentage of that increase in consumption of goods will most likely reflect an increase in demand for the foreign nation goods.

Government Restructures: If a country’s government imposes a particular type of tax (often referred to as a tariff tax) on imported goods from foreign countries, the prices of foreign goods to consumers effectively increases. An increase in prices of imported goods relative to goods produced at domestic country will discourage imports and is expected to increase its current account balance. In addition to tariffs, a government may reduce its imports by enforcing a quota, or a maximum limit on imports.

Foreign Exchange Rate: Foreign exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of other. Since there is an essential symmetry between the two currencies, the exchange rate may be defined in one of the two ways: Cost in domestic currency of purchasing one unit of foreign currency.

That is, domestic currency units per unit of foreign currency. Amount of foreign currency that foreign exchange rate may be bought for one unit of domestic currency. That is foreign currency units per unit of domestic currency.

In general, the foreign exchange rate is determined by the interaction of the market demand curve for and market supply curve of the foreign currency. That is, the exchange rate is determined just like the price of any commodity.

On the demand side,

- One of the principal reasons people desire foreign currencies is to purchase goods and services from another country or to send a gift or investment income payment abroad.

- A second reason is to purchase financial assets in a particular country.

- The third reason people demand foreign currency is to avoid losses or make profits that would arise through changes in the foreign exchange rate.

On the other hand, the total supply of the foreign exchange in a country consists of three sources.

- Firstly, it results from foreigner’s purchasing home exports of goods and services or making unilateral transfers to the home country.

- A second source arises from foreign investment in the home country.

- Finally, foreigner’s purchase of home currency to avoid losses or to make profits from changes in the exchange rate is the third source of supply.

Since the foreign exchange market brings together those people that wish to buy a currency(which represents the demand) with those that wish to sell the currency (which represents the supply), then the exchange rate can easily be determined by the intersection of the demand and supply of the currency.

Nominal exchange rate and Real exchange rate:

The nominal exchange rate E is defined as the number of units of the domestic currency that can purchase a unit of a given foreign currency. It’s called nominal, because it takes into account only the numerical value of the currencies. It doesn’t take into account the purchasing power of the currencies. There is another exchange rate called “real exchange rate” that takes the purchasing power

- A decrease in this variable is termed nominal appreciation of the currency. (Under the fixed exchange rate regime, a downward adjustment of the rate E is termed revaluation.)

- An increase in this variable is termed nominal depreciation of the currency. (Under the fixed exchange rate regime, an upward adjustment of the rate E is called devaluation.)

Determination of the nominal exchange rate coincides with the general definition of the exchange rate and is set on the currency market. It is used in the foreign exchange contracts and is the simplest and the most basic definition of the exchange rate.

However, it is not very suitable for long-term forecasting, because the cost of foreign and national currencies are changing at a time with the change in the overall price level in the country.

By contrast, the real exchange rate R is defined as the ratio of the price level abroad and the domestic price level, where the foreign price level is converted into domestic currency units via the current nominal exchange rate.

Formally, R=(E.P*)/P, where the foreign price level is denoted as P* and the domestic price level as P. A decrease in R is termed appreciation of the real exchange rate, an increase is termed depreciation.

The real rate tells us how many times more or less goods and services can be purchased abroad (after conversion into a foreign currency) than in the domestic market for a given amount. In practice, changes of the real exchange rate rather than its absolute level are important.

In contrast to the nominal exchange rate, the real exchange rate is always ”floating”, since even in the regime of a fixed nominal exchange rate E, the real exchange rate R can move via price-level changes.

Rather than focusing on the nominal exchange rate, it is more sensible to monitor the real exchange rate when assessing the effect of exchange rates on international trade or export competitiveness of a country.

For simplicity, assume that the domestic price level rises by 10%, the foreign price level remains unchanged and the domestic currency depreciates nominally by 10%. Then the real exchange rate, i.e. the ratio of prices at home and abroad, remains unaffected, depreciation of the domestic currency notwithstanding.

Other things held equal in our simplified framework, there would be no change in the demand for imports in the domestic economy and in the demand for exports of the domestic economy abroad.

The real exchange rate is the ratio of the consumer goods basket abroad, transferred from a foreign currency into the national one with help of the nominal exchange rate (the nominal exchange rate multiplied by the price index of a foreign country) and the prices of the consumer goods basket of the same goods in home country.

The index of real exchange rate shows its change adjusted for inflation rate in both countries. If the rate of inflation in home country is higher than foreign one, then the real exchange rate will be higher than nominal one.

Purchasing Power Parity(PPP): Purchasing power parity (PPP) is a theory that says that in the long run (typically over several decades), the exchange rates between countries should even out so that goods essentially cost the same amount in both countries.

The Theory of Purchasing Power Parity explains that there should be no arbitrage opportunities (where price differences between countries can result in profit). Purchasing power parity is used to compare the gross domestic product between countries.

PPP is based on the Law of One Price, which implies that all identical goods should have the same price. It is usually calculated using a similar basket of goods in two countries and is also used to evaluate under-/overvalued currencies.

The basket of goods and services priced for the PPP exercise is a sample of all goods and services covered by GDP. The final product list covers around 3,000 consumer goods and services, 30 occupations in government, 200 types of equipment goods and about 15 construction projects.

A large number of products are provided so as to enable countries to identify the goods and services that are representative of their domestic expenditures.

For example: A loaf of bread in the US costs $2, and that amount in Indian Rupees is Indian Rupee ₹90, but a loaf of bread in India costs around Indian Rupee ₹10–that’s about 20 cents. This creates an arbitrage opportunity where people in India can stock up on bread and bring it to the US, where they can sell it to make a nice profit.

The concept of purchasing power parity says that since they are the same goods, the purchasing power in the two countries should be the same. This doesn’t mean the exchange rate should be equal to one; it means the ratio of price to exchange rate should be one. In this example, it implies that exchange rate should be $2 = Indian Rupee ₹10, and $1 = Indian Rupee ₹5. So, the Rupee here is undervalued.

Q) Considering the following statements:

1. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) exchange rates are calculated by the prices of the same basket of goods and services in different countries.

2. In terms of PPP dollars, India is the sixth largest economy in the world.

Which of the statements given above is/ are correct?

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 only

(c) Both 1 and 2

(d) Neither 1 nor 2

Exchange Rate Indices: NEER and REER

As country’s currency can be compared with any other currency and a given country’s currency can be expected to appreciate compared some currencies while expected to depreciate against some other currency.

But can we generalize, whether a given country currency is expected to appreciate or depreciate? This can be done so by comparing the currency value of any country with the currency value of its major trading partners.

Two types of Exchange rate indices are calculated.

Nominal effective Exchange Rate (NEER):

- The Reserve Bank of India tabulates the rupee’s Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) in relation to the currencies of 36 trading partner countries.

- This is a weighted index — that is, countries with which India trades more are given a greater weight in the index.

- A decrease in this index denotes depreciation in rupee’s value whereas an increase reflects appreciation.

- There is one more measure that is even better at capturing the actual change. This is called the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) and is essentially an improvement over the NEER because it also takes into account the domestic inflation in the various economies.

- The REER is the weighted average of NEER adjusted by the ratio of domestic prices to foreign price.

Impact of Inflation on Exchange Rate.

- Many factors affect the exchange rate between any two currencies ranging from the interest rates to political stability (less of either results in a weaker currency). Inflation is one of the most important factors.

- Illustration: Imagine that the Rupee-Dollar exchange rate was exactly 1 in the first year. This means that with Rs 100, one could buy something that was priced at $100 in the US. But suppose the Indian inflation is 20% and the US inflation is zero. Then, in the second year, an Indian would need Rs 120 to buy the same item priced at $100, and the rupee’s exchange rate would depreciate (reduce in value) to 1.20.

Real effective Exchange Rate (REER): Real effective exchange rate is defined as “a weighted average of nominal exchange rates adjusted for relative price differential between the domestic and foreign countries, relates to the purchasing power parity (PPP) hypothesis”.

As the definition highlights, REER takes price differential and inflation into account and, therefore, is said to be a better indicator of the competitiveness of the country in terms of exchange rates. REER is calculated by multiplying NEER with the effective relative price indices of trading partners.

The relative price indices are calculated by the weighted wholesale price index of trading partners and the consumer price index for the home country).

Depending on the changing profile of export-import partners, countries may periodically revise the trading partner’s currency list. It is interesting to note here that RBI was calculating NEER and REER with respect to 36 currencies. In other words, RBI was considering India’s trading partners to be 36.

What is the connection between Balance of Payments and the value of Rupee?

The balance of payment account is that it shows the amount of foreign currency India is receiving and paying. The difference between the total dollar receipts (through exports of goods, services and foreign capital obtained) and payments (through imports of goods, services and outflow of capital) shows how much net foreign currency India is getting.

Higher the amount of foreign currency receipts compared to payments, it means foreign currency is in adequate quantity and the price of foreign currency may come down in the market. We call this as appreciation (for example, previously you should pay Rs 65 to get $1 and now you have to pay just Rs 50 to get $1).

On the other hand, if India’s payments are higher than receipts of (foreign currencies) it means that we have to find additional dollars to pay our extra payments. Here, the price of foreign currency will go up in the market as its availability is low (Previously Rs 65 to get $1 and now, Rs 70 to get $1). We call this as depreciation of rupee. Depreciation and appreciation are explained from the angle of domestic currency.

What is Depreciation?

Depreciation of the rupee refers to the decrease in the external value of the domestic currency occurred due to the operation of market forces.

Here, the exchange rate is moving with demand and supply of dollar. Depreciation happens under a flexible exchange rate system or under a managed floating exchange rate system. (Eg. 1$ = Rs 40 to 1$ = Rs 50).

Depreciation Vs Devaluation: Both devaluation and depreciation cause the value of domestic currency to fall vis-a-vis any foreign currency. However, depreciation occurs in the market-determined exchange rate system and devaluation occurs in the fixed exchange rate system.

Causes of Rupee Depreciation

The following can be the causes behind depreciation:

- Rise in imports: In the case of rise in imports, importers would require more foreign currency to pay for imports. Demand for foreign currency (and corresponding supply of domestic currency) leads to depreciation of the domestic currency.

- Fall in exports: In the case of fall in exports, exporters would have less foreign exchange earnings. They get their foreign exchange earnings converted to Indian rupee. Thus, when exports fall, the demand for rupee decreases.

- Fall in remittances: Fall in remittances from Indians working abroad leads to lesser foreign exchange availability in India. The recipient of foreign exchange, therefore, demands less amount of rupee to replace dollar.

- Withdrawal of foreign investment: When a foreign investor withdraws investment from India, he/she demands foreign currency in place of rupee. Thus, there is supply of rupee but demand of foreign currency.

- Foreign loan repayment: Foreign loan repayment and withdrawal of foreign investment function in the similar manner and have similar foreign exchange rate implications.

Consequences of Rupee Depreciation

- Trade deficit will widen because of costlier imports, worsening the current Account deficit.

- Spending on any kind of foreign exchange denominated spending will increase. Capital inflow will slow or reverse.

- Spending on discretionary goods will increase.

- Forex reserves could fall putting pressure on rupee.

- In case of weak demand companies may not be able to pass on higher inputs costs.

- The government and the RBI have issued a series of measures in recently designed to reduce the current account deficit and bolster the rupee, including increases in the import duty on gold, restrictions on outward direct investment by Indian companies and individuals.

- Exports are unable to leverage the weak rupee fast enough given the speed of its descent. In fact many exporters are caught out because of fixed price contracts in rupees wherein they cannot get the benefits of its rapid fall. The balance of payments is tilting sharply against us.

- The Indian stock- market will take a hiding as opposed to a beating.

- Global rating agencies will revise our rating downwards to “junk” status, making international borrowing difficult and even more expensive.

How to contain Depreciation of Rupee?

- The RBI which manages the rupee’s movement buys US dollars from market when the rupee strengthens and sells the dollars when rupee weakens. RBI tries to maintain a balance by taking in to effect all external and internal factors

- RBI will take steps to attract more capital flows.

- The RBI can ensure that export earnings come back to the country on time while importers should be urged not to rush in to buy dollars in advance. Alternatively, asking the importers to hedge can be attempted though it cannot be made mandatory.

- The government should focus on exports and to the extent possible, especially on the tax credit/refund part, clear the coast for exporters. SMEs (small and medium enterprises) which are dominant in the export market have had tax refund issues and this needs to be sorted out.

- As oil is the major import component, and whose prices are rising, a separate window needs to be opened for selling dollars. Also, hedging processes must be put in place to ensure that the purchases are in order. OMCs (oil marketing companies) do take forward contracts to buffer against price changes, but to the extent there are open positions hedging should be made mandatory.

- The capital flows need to be monitored proactively and this is where FPIs (foreign portfolio investments) matter. The strong inflow of FPIs has the power to rein in the rupee.

Q) Which one of the following is not the most likely measure the Government/RBI takes to stop the slide of Indian rupee?

(a) Curbing imports of non-essential goods and promoting exports

(b) Encouraging Indian borrowers to issue rupee denominated Masala bonds

(c) Easing conditions relating to external commercial borrowing

(d) Following an expansionary monetary policy

Q) If another global financial crisis happens in the near future, which of the following actions/policies are most likely to give some immunity to India?

1. Not depending on short-term foreign borrowings

2. Opening up to more foreign banks

3. Maintaining full capital account convertibility

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 only

(b) 1 and 2 only

(c) 3 only

(d) 1,2 and 3

Q) In the context of India, which of the following factors is/ are contributor/contributors to reducing the risk of a currency crisis?

1. The foreign currency earnings of India’s IT sector.

2. Increasing the government expenditure.

3. Remittances from Indians abroad.

Select the correct answer using the code given below.

(a) 1 only

(b) 1 and 3 only

(c) 2 only

(d) 1,2 and 3 only

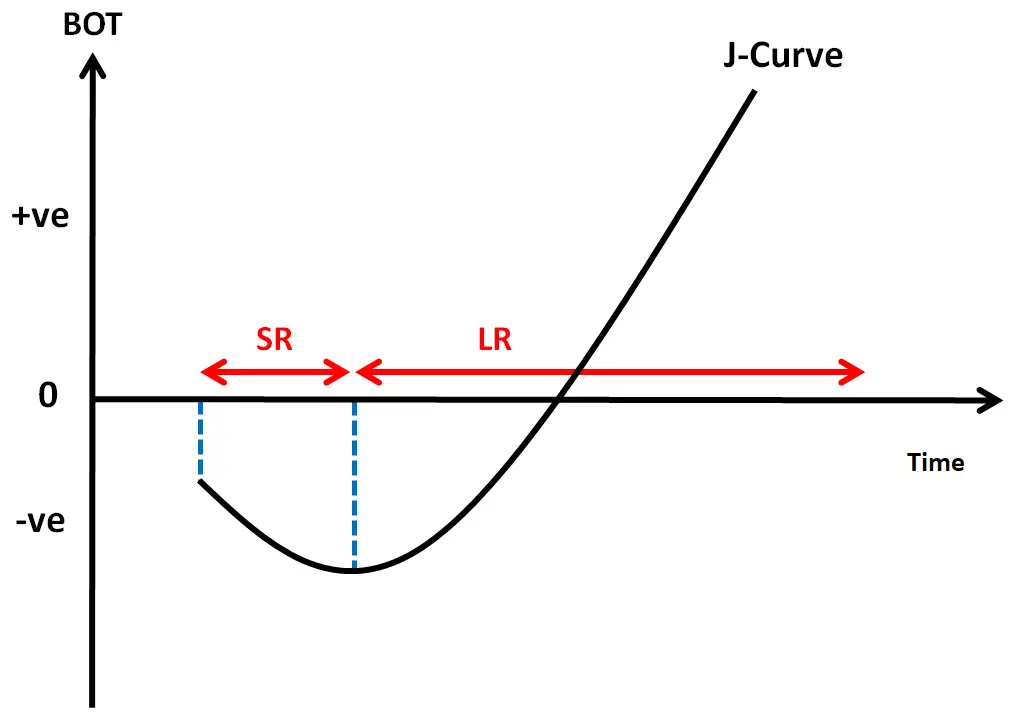

J Curve Effect: A J-curve is a trendline that shows an initial loss immediately followed by a dramatic gain. In a chart, this pattern of activity would follow the shape of a capital “J”.

The J-curve effect is often cited in economics to describe, for instance, the way that a country’s balance of trade initially worsens following a devaluation of its currency, then quickly recovers and finally surpasses its previous performance.

In economics, it is often used to observe the effects of a weaker currency on trade balances. The pattern is as follows:

- Immediately after a nation’s currency is devalued, imports get more expensive and exports get cheaper, creating a worsening trade deficit (or at least a smaller trade surplus).

- Shortly thereafter, the sales volume of the nation’s exports begins to rise steadily, thanks to their relatively cheap prices.

- At the same time, consumers at home begin to buy more locally-produced goods because they are relatively affordable compared to imports.

- Over time, the trade balance between the nation and its partners bounces back and even exceeds pre-devaluation times.

The devaluation of the nation’s currency had an immediate negative effect because of an inevitable lag in satisfying greater demand for the country’s products. When a Country’s currency appreciates, economists note, a reverse J-curve may occur.

The country’s exports abruptly become more expensive for importing countries. If other countries can fill the demand for a lower price, the stronger currency will reduce its export competitiveness. Local consumers may switch to imports, too, because they have become more competitive with locally-produced goods.

Trade in domestic currencies

Internationalization of Rupee

Rupee-Rouble Trade

SWIFT

- Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) is a member-owned cooperative that provides safe and secure financial transactions for its members.

- This payment network allows individuals and businesses to take electronic or card payments even if the customer or vendor uses a different bank than the payee.

- SWIFT is the largest and most streamlined method for international payments and settlements.

- SWIFT works by assigning each member institution a unique ID code (a BIC number) that identifies the bank name and the country, city, and branch.

- SWIFT has been used to impose economic sanctions on Iran, Russia, and Belarus.

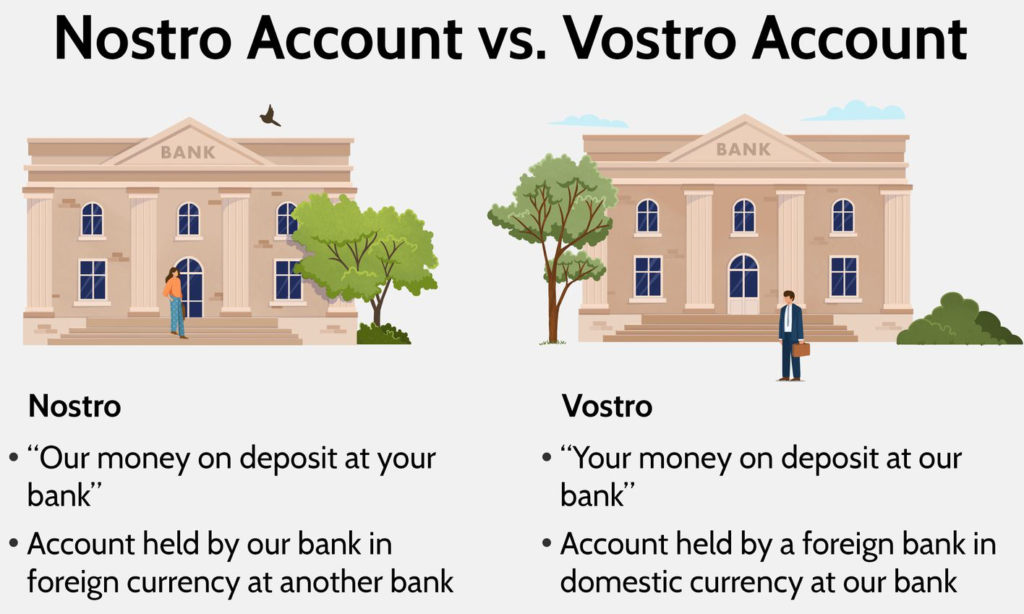

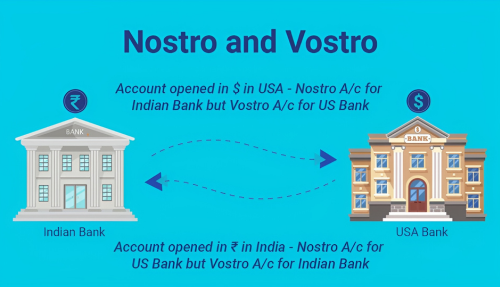

VOSTRO and NOSTRO Accounts

Correspondence Banking:

Challenges in Internationalization of Rupee:

What is Appreciation?

Appreciation of the rupee refers to the increase in the external value of the domestic currency occurred due to the operation of market forces. Here, the exchange rate is moving in accordance with the demand and supply of dollar. Appreciation happens under a flexible exchange rate system or under a managed floating (Eg. 1$ = Rs 65 to 1$ = Rs 50).

Appreciation Vs Revaluation

Revaluation is a term which is used when there is a rise in currency value in relation with a foreign currency in a fixed exchange rate. In the floating exchange rate regime, the correct term would be appreciation. Altering the face value of a currency without changing its foreign exchange rate is a redenomination, not a revaluation.

Causes of Appreciation of Rupee

The appreciation of currency can occur on account of any of the following reasons:

- Fall in imports

- Rise in exports

- Rise in remittances

- Increase in foreign investment

- Receipt of fresh loans from external sources

The causes responsible for appreciation of currency are exactly opposite to the causes responsible for depreciation of currency.

Consequences of Rupee Appreciation

- For an economy like India that relies on imports for more than 80% of its daily crude requirement, the strong rupee comes as a major blessing in disguise. A stronger rupee means lower landed cost of crude oil, which is anyways expressed in dollar terms. A lower landed cost of oil will not only be anti-inflationary but will also reduce the burden on the government finances.

- On the subject of government finances, the fiscal deficit and the revenue deficit are largely driven by the INR movement versus the dollar. Lower oil import bill means that India can afford to run a lower revenue deficit as well as a lower fiscal deficit. That explains why the government can afford to focus on fiscal discipline. When fiscal deficit and revenue deficit are in control, it is positive from the perspective of external credit ratings for the economy.

- Import intensive sectors tend to benefit. A stronger rupee makes imports more favourable and is especially suitable for sectors like capital goods and telecom where there is a strong import component. A strong rupee makes imports cheaper and generally tends to be positive for import intensive sectors. However, in case of industries like gems & jewellery and textiles, where there is an export component, the benefits of cheaper imports tend to get neutralized.

- On the other hand, export driven sectors like IT, textiles and pharma tend to suffer from a strong rupee.

- Foreign portfolio flows are largely predicated on the strength of the INR. A strong rupee means that FPIs do not lose out their nominal gains due to currency depreciation. A strengthening INR induces FPIs to rush into India as they get the dual benefit of above average nominal returns and currency dividends. This works as a cycle wherein a strong rupee attracts more FPI flows and these FPI flows in-turn make the INR stronger.

How to contain Appreciation of Rupee?

- In the case of appreciation of rupee, exports from India are discouraged and imports to India are encouraged. To reverse the trend of decreasing exports and increasing imports, the RBI intervenes and purchases dollar in exchange for Indian rupee.

On account of increase in demand for dollar, the value of dollar rises. However, purchase of dollar in exchange of rupee adds rupee in the economy, leading to increase in money supply and consequently, inflation. - As the rupee appreciate more investment more investments comes in to the country which in turn leads to more money in the market. This money should be used to benefit India by creating funds to invest in strategic industries abroad, mainly in US and EU.

The funds can created through consortium of big Indian Business Houses (IBH) or through Strategic Investment Fund Companies (SIFC). - Money may be raised through public issues and used by IBH or SIFC in buying 20% or more stake in strategic industries, where these organizations can influence decisions made in those companies like outsourcing and purchasing.

- Money may be raised through public issues and used to invest in Strategic Industries can be anything from retail giants, toy companies, auto manufacturers to mining companies.

- The public issues will take away excess money from general public which will help in curtailing inflation. In addition money will be invested in US companies resulting in depreciation of Indian currency against US dollar.

Market Sterilization Scheme

|

Implications of Depreciation and Appreciation of Rupee |

||

|

Stakeholders |

Depreciation |

Appreciation |

|

Exporters |

Deprecaition of rupee beneifts exporters and thus promotes exports. Let us say that the value of exports is $1000.The conversion rates before and after depreciation were Rs.65/$1 and Rs.67/$1 respectively. The export earnings before and after depreciation were Rs.65,000 and Rs.67,000 respectively. Usually domestic inflation also contributes to depreciation of currency. Thus partial benefit arising on account of depreciation od currency is countered by high costs of production |

Appreciation of rupee discourages exports. Let us say that the value of exports is $1000.The conversion rates before and after appreciation were Rs.65/$1 and Rs.63/$1 respectively. The export earnings before and after appreciation were Rs.65,000 and Rs.63,000 respectively. |

|

Importers |

Depreciation of rupee makes imports costlier. Let us say that the value of imports is $1000. the conversion rates before and after depreciation Rs.65/$1 and Rs.67/$1 respectively. The import outgo before and after depreciation were Rs.65,000 and Rs.67,000 respectively. |

Appreciation of rupee makes imports cheaper. Let us say that the value of imports is $1000. the conversion rates before and after depreciation Rs.65/$1 and Rs.63/$1 respectively. The import outgo before and after appreciation were Rs.65,000 and Rs.63,000 respectively. |

|

Loan Repayment |

Depreciation of rupee makes loan repayment costly |

Appreciation of rupee makes loan repayment cheaper |

|

Foreign Investment |

Depreciation of rupee promotes foreign investment. A foreign investor would be able to make larger investment with less foreign currency. |

Appreciation of rupee discourages foreign investment. A foreign investor would be able to make lesser investment with more foreign currency. |

Convertibility of Rupee

Currency convertibility refers to the freedom to convert the domestic currency into other internationally accepted currencies and vice versa.

Current account convertibility means freedom to convert domestic currency into foreign currency and vice versa to execute trade in goods and invisibles.

On the other hand, capital account convertibility implies freedom of currency conversion related to capital inflows and outflows.

Currency convertibility is of two types:

- Current account convertibility

- Capital account convertibility

Q) Convertibility of rupee implies

(a) Being able to convert rupee notes into gold

(b) Allowing the value of rupee to be fixed by market forces

(c) Freely permitting the conversion of rupee to other currencies and vice versa

(d) Developing an international market for currencies in India

Current Account Convertibility: Current account convertibility means freedom to convert domestic currency into foreign currency and vice versa to execute trade in goods and invisibles.

Current account convertibility allows the exporter and importers to convert the currency into foreign exchange for all the trade related purposes.

It allows to convert the currency for foreign studies, medical treatment, and buying any goods and services other than of capital nature.

Current account convertibility in Indian economy: As a part of the economic reforms introduced during and after 1991, Government of India has initiated steps to allow partial convertibility of rupee into foreign currency under liberalised exchange management scheme in which 60 per cent of all receipts on current account could be converted freely into rupees at market determined exchange rate quoted by authorised dealers, whereas the remaining 40% should be surrendered to the Reserve Bank of India at the rates determined by it.

Here current account transactions include import and exports of all goods and services. This 40% of foreign currency was meant for fulfilling the foreign exchange needs of government and to make payments for the Imports of essential commodities by the government.

That’s why this was called as Dual exchange rate system. Later in 1993 full current account convertibility was allowed by the government to provide the full conversion of foreign receipts on current account in to Indian rupees.

Capital Account Convertibility: It means ability to convert the foreign exchange in to Indian rupees and vice versa on account of all capital transactions at a rate determined by the free flow of market and not by a country’s monetary controlling authority (RBI in India).

A capital transaction is one that deals with non-current assets or liabilities, such as:

- Fixed assets (ex. buying and selling equipment),

- Certain kinds of investments (ex. the buying and selling of securities intended to be held for long-term investment),

- Long-term debt (ex. the acquisition and paying off of loans that have terms longer than one year), and

- Equity transactions (ex. dividend payments and share purchases

Capital Account Convertibility is not just the currency convertibility freedom, but more than that, it involves the freedom to invest in financial assets of other countries.

The Committee on Capital Account Convertibility (1997, Chairman Dr S S Tarapore) in its report has given a working definition for the CAC which is as following. “CAC refers to the freedom to convert local financial assets into foreign financial assets and vice versa at market determined rates of exchange.

It is associated with changes of ownership in foreign/domestic financial assets and liabilities and embodies the creation and liquidation of claims on, or by, the rest of the world.”

Capital account convertibility is thus the freedom of foreign investors to purchase Indian financial assets (shares, bonds etc.) and that of the domestic citizens to purchase foreign financial assets.

It provides rights for firms and residents to freely buy into overseas assets such as equity, bonds, property and acquire ownership of overseas firms besides free repatriation of proceeds by foreign investors.

Q) The Capital Account Convertibility of the Indian Rupee implies:

(a) That the Indian Rupee can be exchanged by the authorised dealers for travel

(b) That the Indian Rupee can be exchanged for any major currency for the purpose of trade in goods and services

(c) That the Indian Rupee can be exchanged for any major currency for the purpose of trading financial assets

(d) None of the above

Hard Currencies or Fully convertible Currencies: Hard currency refers to money that is issued by a nation that is seen as politically and economically stable. Hard currencies are widely accepted around the world as a form of payment for goods and services and may be preferred over the domestic currency.

A hard currency is expected to remain relatively stable through a short period of time, and to be highly liquid in the forex or foreign exchange (FX) market. The most tradable currencies in the world are the U.S. dollar (USD), European euro (EUR), Japanese yen (JPY), British pound (GBP), Swiss franc (CHF), Canadian dollar (CAD) and the Australian dollar (AUD). All of these currencies have the confidence of international investors and businesses because they are not generally prone to dramatic depreciation or appreciation.

The U.S. dollar stands out in particular as it enjoys status as the world’s foreign reserve currency. For this reason, many international transactions are done in U.S. dollars. Moreover, if a country’s currency begins to soften, citizens will begin holding U.S. dollars and other safe haven currencies to protect their wealth.

Q) Which one of the following is the correct sequence of decreasing order of the given currencies in terms of their value in Indian Rupees?

(a) US dollar, Canadian dollar, New Zealand dollar, Hong Kong dollar

(b) US dollar, New Zealand dollar, Canadian dollar, Hong Kong dollar

(c) US dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Canadian dollar, New Zealand dollar

(d) Hong Kong dollar; US dollar, New Zealand dollar, Canadian Dollar.

The First Tarapore Committee on Capital Account Convertibility

A committee on capital account convertibility was setup by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) under the chairmanship of former RBI deputy governor S.S. Tarapore to “lay the road map” to capital account convertibility. In 1997, the Tarapore Committee had indicated the preconditions for Capital Account Convertibility.

The three crucial preconditions were fiscal consolidation a mandated inflation target and strengthening of the financial system. The five-member committee has recommended a three-year time frame for complete convertibility by 1999-2000.

The highlights of the report including the preconditions to be achieved for the full float of money are as follows:-

Pre-Conditions:

- Gross fiscal deficit to GDP ratio has to come down from a budgeted 4.5 per cent in 1997-98 to 3.5% in 1999-2000.

- A consolidated sinking fund has to be set up to meet government’s debt repayment needs; to be financed by increased in RBI’s profit transfer to the govt. and disinvestment proceeds.

- Inflation rate should remain between an average 3-5 per cent for the 3-year period 1997-2000

- Gross NPAs of the public sector banking system needs to be brought down from the present 13.7% to 5% by 2000. At the same time, average effective CRR needs to be brought down from the current 9.3% to 3%

- RBI should have a Monitoring Exchange Rate Band of plus minus 5% around a neutral Real Effective Exchange Rate RBI should be transparent about the changes in REER

- External sector policies should be designed to increase current receipts to GDP ratio and bring down the debt servicing ratio from 25% to 20%

- Four indicators should be used for evaluating adequacy of foreign exchange reserves to safeguard against any contingency. Plus, a minimum net foreign asset to currency ratio of 40 per cent should be prescribed by law in the RBI Act.

The above committee’s report was not translated into any actions. India is still a country with partial convertibility. However, some important measures in “that direction” were taken and they are summarized as below:

- The Indian Corporate were allowed full convertibility in an automatic route up to the $ 500 million overseas ventures. This means that the limited companies were allowed to invest in foreign countries.

- Indian corporate were allowed to prepay their external commercial borrowings via automatic route if the loan is above $ 500 million.

- Individuals were allowed to invest in foreign assets , shares up to $ 2, 00, 000 per year.

- Unlimited amount of Gold was allowed to be imported

The Second Tarapore Committee on Capital Account Convertibility

This report advocates a three-phased approach, the first phase beginning this year (2006-07), the second during 2007-09 and the last ending 2011.

Following were some important recommendations of this committee:

- The ceiling for External Commercial Borrowings (ECB) should be raised for automatic approval.

- NRI should be allowed to invest in capital markets

- NRI deposits should be given tax benefits.

- Improvement of the Banking regulation.

- FII (Foreign Institutional Investors) should be prohibited from investing fresh money raised to participatory notes.

- Existing PN holders should be given an exit route to phase out completely the PN notes.

At present the rupee is fully convertible on the current account, but only partially convertible on the capital account.

Q) Consider the following statements: Full convertibility of the rupee may mean:

1. Its free float with the international currencies

2. Its direct exchange with any other international currency at any prescribed place inside and outside the country

3. It acts just like any other international currency

Which of these statements is/are correct?

(a) 1 and 2

(b) 1 and 3

(c) 2 and 3.

(d) 1,2 and 3

Q) Consider the following statements: The Indian rupee is fully convertible:

1. In respect of Current Account of Balance of payment

2. In respect of Capital Account of Balance of payment

3. Into gold

Which of these statements is/are correct?

(a) 1 alone

(b) 3 alone

(c) 1 and 2

(d) 1,2 and 3

Should India go for full Capital Account Convertibility or for partial Capital Account Convertibility?

The East Asian Financial crisis

The East Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 was a financial crisis that affected many Asian countries, including South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and the Philippines. After posting some of the most impressive growth rates in the world at the time, the so-called “tiger economies” saw their stock markets and currencies lost about 70% of their value.

The Asian financial crisis, like many other financial crises before and after it, began with a series of asset bubbles. Growth in the region’s export economies led to high levels of foreign direct investment, which in turn led to soaring real estate values, bolder corporate spending, and even large public infrastructure projects – all funded largely by heavy borrowing from banks. Of course, ready investors and easy lending often lead to reduced investment quality, and excess capacity soon began to show in these economies.

The Federal Reserve also began to raise its interest rates around this time to counteract inflation, which led to less attractive exports (for those with currencies pegged to the dollar) and less foreign investment. The tipping point was the realization by Thailand’s investors that its property market was unsustainable, which was confirmed by Somprasong Land’s default and Finance One’s bankruptcy in 1997.

After that, currency traders began attacking the Thai baht’s peg to the U.S. dollar, which proved successful and the currency was eventually floated and devalued.

Following this devaluation, other Asian currencies including the Malaysian ringgit, Indonesian rupiah, and Singapore dollar all moved sharply lower. These devaluations led to high inflation and a host of problems that spread as wide as South Korea and Japan.

The Asian financial crisis was ultimately solved by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which provided the loans necessary to stabilize the troubled Asian economies. In late 1997, the organization had committed over $110 billion in short-term loans to Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea to help stabilize the economies – more than double its largest loan earlier.

In exchange for the funding, the IMF required the countries to adhere to strict conditions, including higher taxes, reduced public spending, privatization of state-owned businesses and higher interest rates designed to cool the overheated economies.

Some other restrictions required countries to close illiquid financial institutions without concern for employment. By 1999, many of the countries affected by the Asian Financial Crisis showed signs of recovery with gross domestic product (GDP) growth resuming.

Many of the countries saw their stock markets and currency valuations dramatically reduced from pre-1997 levels, but the solutions imposed set the stage for the re-emergence of Asia as a strong investment destination.

Q) Global capital flows to developing countries increased significantly during the nineties. In view of the East Asian financial crisis and Latin American experience, which type of inflow is good for the host country?

(a) Commercial loans

(b) Foreign Direct Investment

(c) Foreign Portfolio Investment

(d) External Commercial borrowings

The Asian financial crisis has many important lessons that are applicable to events happening today and events likely to occur in the future.

Here are some important takeaways:

- Watch Government Spending: Government dictated spending on public infrastructure projects and guidance of private capital into certain industries contributed to asset bubbles that may have been responsible for the crisis.

- Re-Evaluate Fixed Exchange Rates: Fixed exchange rates have largely disappeared, except for the instance where they use a basket of currencies, since flexibility may be needed in many cases to avert a crisis like these.

- Concerns about the IMF: The IMF took a lot of criticism after the crisis for being too strict in its loan agreements, particularly with successful economies like South Korea. Moreover, the moral hazard created by the IMF may be a cause of the crisis.

- Always Beware of Asset Bubbles: Investors should carefully watch out for asset bubbles in the latest/hottest economies around the world. All too often, these bubbles end up popping, and investors are caught off-guard.

The Asian financial crisis began with a series of asset bubbles that were financed with foreign direct investment. When the Federal Reserve began to hike interest rates, foreign investment dried up, and high asset valuations were difficult to sustain.

Equity markets moved significantly lower, and the International Monetary Fund eventually stepped in with billions of dollars’ worth of loans to stabilize the market. The economies eventually recovered, but many experts have been critical of the IMF for its strict policies that may have exacerbated the problems.

Mains Previous Year Questions:

Q) The craze for gold in Indians has led to a surge in import of gold in recent years and put pressure on the balance of payments and external value of the rupee. In view of this, examine the merits of the Gold Monetization Scheme.

Q) Justify the need for FDI for the development of the Indian economy. Why is there a gap between MOUs signed and actual FDIs? Suggest remedial steps to be taken for increasing actual FDIs in India.

Q) Foreign direct investment in the defence sector is now said to be liberalized. What influence this is expected to have on Indian defence and economy in the short and long-run?

Q) Though India allowed Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in what is called multi-brand retail through the joint venture route in September 2012, the FDI, even after a year, has not picked up. Discuss the reasons.

Q) How would the recent phenomena of protectionism and currency manipulations in world trade effect macroeconomic stability of India?